Bark’s Bytes #23 | Virtual Institutions

As you read the following, I ask that you allow this “old dog” to use general concepts, outdated verbiage, and approximate timeframes in telling this story of how I came to work in the field of human services and how it relates to the issues we are facing at the legislature today.

In the winter of 1978, my friend John Selvog drove a bus route in St. Cloud, MN that transported children with “mental retardation” from their family homes to a segregated school and back. As Christmas approached John realized it was unlikely that these kids would see Santa at the mall like their peers. Together we convinced the Dayton’s Department Store to donate candy and smalls gifts for each of the kids and to loan us their Santa suit for a night of visits. With me suited up as Santa, John drove us to each of the kid’s homes where we delivered the gifts to the delight of each family and the kids got to hug Santa and whisper their gift wishes. Something resonated with me that evening and I dropped out of college for the spring semester so I could volunteer as a teacher’s assistant at the segregated school the kids attended.

Returning to St. Cloud State in the fall of 1979 I declared my major as a Recreation Therapist which required two more semesters and a 400 hour volunteer internship. Getting married in November of that year my internship options were limited as my wife Mary had a full-time job in St. Cloud that we needed until I graduated. I was fortunate to be accepted for an internship at Brainerd State Hospital and began in May of 1980 under the supervision of Blaine Church. At the time we only had one car which Mary needed for her job in St. Cloud. As a result, I hitch-hiked every Sunday afternoon from St. Cloud to Brainerd, lived in a basement classroom in building #7, and hitch-hiked back to St. Cloud every Friday afternoon for 10 weeks. Without a car, I literally lived and worked 24/7 in building #7 unless we took clients out into the community. From this experience I got a memorable lesson on the reality of “institutional retardation”.

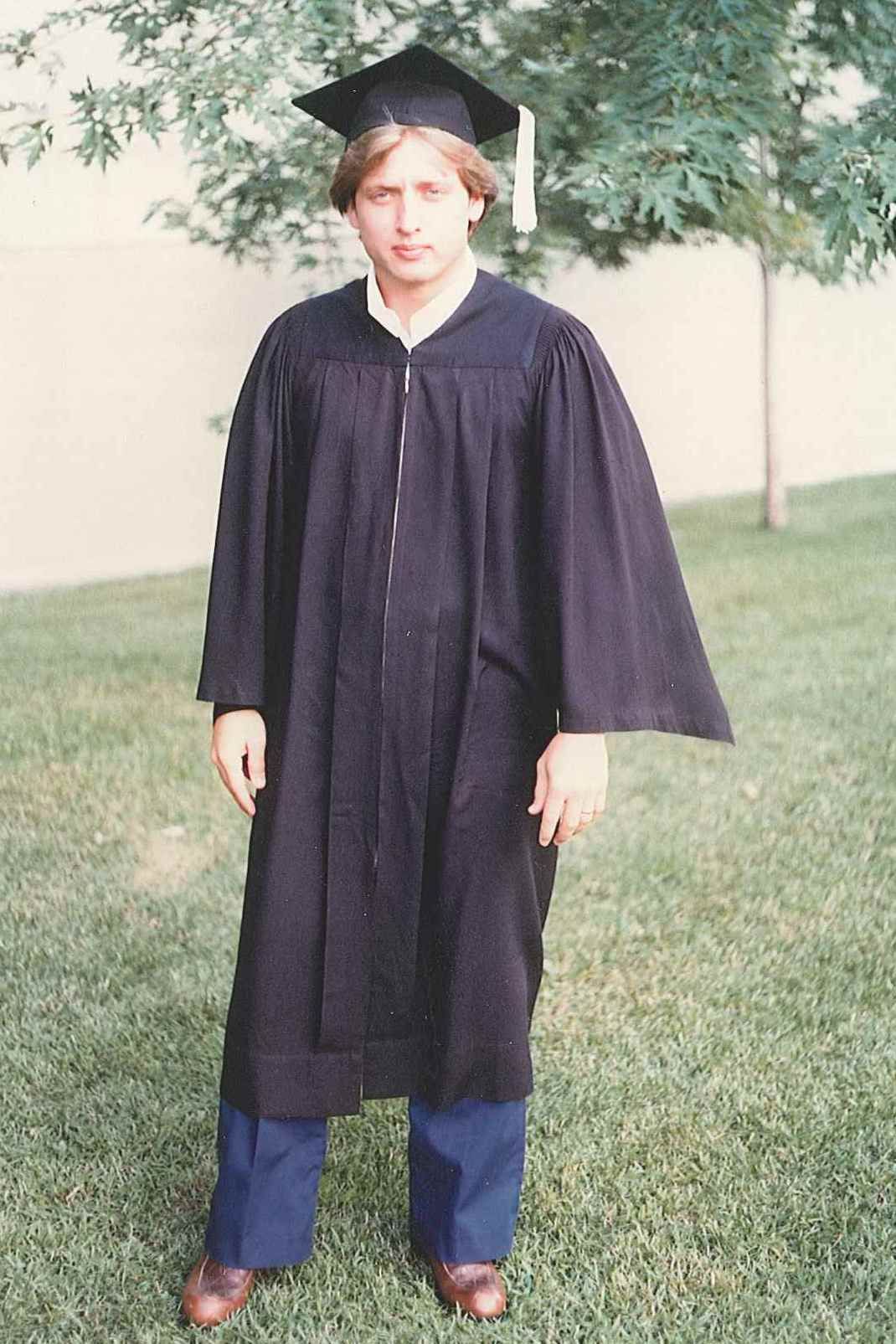

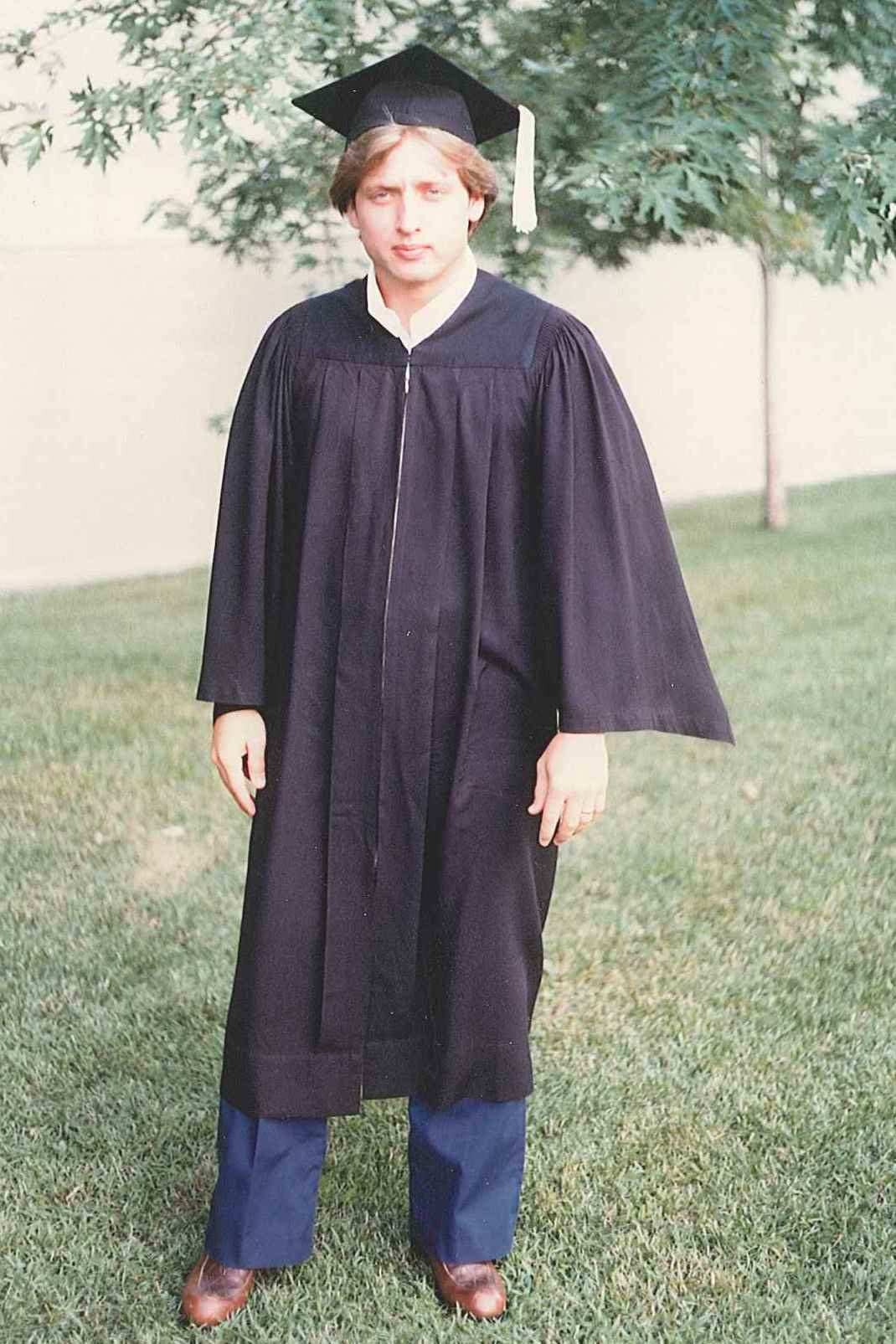

I graduated in August of 1980 and we moved to the Twin Cities where I was hired as a Recreation Therapist at the Greenbrier Home in East St. Paul. After a few years in this position I switched to an administrative track and eventually became the Administrator in 1984. Greenbrier was an Intermediate Care Facility for Mental Retardation (ICF/MR) for 172 men, many of which attended Merrick, Inc. Despite the best of intentions, Brainerd State Hospital and Greenbrier Home were both institutions. In many cases institutions are good things in that they are an organization, establishment, foundation, society, or the like devoted to the promotion of a particular cause or program, especially one of public, educational, or charitable character. However, they are not good homes in any sense of the word.

In the early 1980’s Dr. Warren H. Bock was the interim Disability Services Director for the MN Department of Human Services (DHS) and hired Cindie Becker from Washington State for the sole purpose of getting waivered services approved in Minnesota. Together they submitted the federal application, wrote state statute, and issued requests for proposals to the provider community. After a federal ICF/MR audit, and realizing the future of waivered services, in collaboration with Ramsey County I led an effort to downsize Greenbrier by moving all of the residents into Supported Living Services (SLS) group homes. Concurrently, I formed a company called Focus Homes, Inc., that became an SLS provider to many of these men and eventually served more than 200 people in 65 homes throughout 12 counties. In 1990 I joined Dr. Bock in his consulting practice until I was hired as the Executive Director of Merrick, Inc., in 1998.

From my view, the primary objective of the “waiver” was to permit the state to offer more flexible services with almost a single requirement that it only had to cost less than the existing institutional option. For more than 25 years Minnesota has expanded its waiver options, reduced the use of institutional programs, and discharged nearly every citizen with a developmental or intellectual disability from the state hospital system. Unfortunately, for the past few years the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and DHS have been pushing to move from a social service to a medical service model; and the proposed Disability Waiver Rate System (DWRS) is just one element of this impending change. Having been part of the DWRS workgroup process since 2009, it is my feeling that the new rate frameworks will result in the waiver becoming an institutional service. Apparently we believe that somehow we can annually assess a client’s needs across the domains of communication, behavior, medical, & mental health to prescribe supports needed in the residential, day, and transportation programs. Like you, I have had to fill out those health history questionnaires whenever I see a new clinician and no matter the length or specificity they never really capture my entire life. How is it we can precisely capture the often complex needs of the folks we serve and when was the last time you heard a client say they need a 1:6 staff to client ratio? Moreover, providers will not be able to offer services for less having to accept the rate calculated. Remember George Corporal and the Glass Service Company? When insurance companies decided to pay a flat rate for glass replacement, George offered a box of steaks to customers because he couldn’t compete on price. If we cannot negotiate our rates will we have to offer extras like movie tickets, dinner coupons, and event passes to attract clients to our programs?

I agreed to participate on the DWRS workgroups hoping that I could help influence a good outcome. That did not happen in my opinion. What is being proposed is based on a myth that recipients have a condition, on a finite list, that can be treated with a prescribed course of action, in the same manner by all providers, at a known cost, and the person will get what they need for a basic quality life. It is medical model that just won’t work and if the consequences weren’t so serious it would be silly. DHS reports that in SFY ’10 it spent approximately $160 million on DT&H program and transportation services for almost 16,000 recipients. According to Bert Blyleven’s California math that is $10,000 per client, about $42 a day, or $7 an hour for 6 hours of program services including transportation to and from the program. So, using the bell curve let’s start with $42 as the median per diem, adjust up/down by the standard deviations until the budget is spent, and then allocate that amount to clients in an annual budget to determine what supports they want to purchase so they can discuss options with a number of providers. This won’t happen because DHS believes CMS won’t allow waivers to be this individual and flexible. Still, policymakers need to remember that every penny of the federal financial participation given to Minnesota comes from taxes our citizens pay to the federal government and someone with State authority needs to have the moxie to say enough is enough and we are going to do what is right and practical. We are about to implement a rate framework that is a virtual checklist institutionalizing how funding is approved and we should know by now that funding has everything to do with the flexibility of services. At this point I don’t think we can stop the rate framework train from leaving the station. However, over the next three to four years of implementation we can push back to ensure that the assessment used to inform the rate framework is a person-centered process and work with advocates to get the funding in the hands of the recipients so they can decide both the services and providers they want.